By Kevin Plummer

Article from the Toronto Star (July 10, 1964).

“There is no state that has come to the defense of the free world more readily than the State of Alabama,” George Wallace thundered from a podium in Maple Leaf Gardens, an invited guest speaker at the Lions Club’s international convention in July 1964. “We are interested in the welfare of all mankind. We are not racists. We have no ill feeling towards any man because of race, creed, colour, or religion. Anyone who despises another man on these grounds despises God’s handiwork.”

“Civil rights used to be called confiscation,” the Alabama governor continued, speaking just a year after Bull Connor turned high-pressure fire hoses and police dogs against non-violent protestors in Birmingham, and a year before the Selma to Montgomery marches. “Social justice used to be called socialism. And an oligarchy is now called a benevolent autocracy. What will the people call our federal Government? They will call it a federal tyranny.”

As the arch-segregationist spoke with the passion of a pulpit-thumping revivalist, demonstrators marched outside the arena—carrying placards with slogans like “Feed Wallace to the Lions”—protesting that Lions International had given Wallace a Toronto platform from which to promote his anti-Civil Rights agenda.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, municipal officials tirelessly promoted Toronto as a destination for large-scale conventions. Torontonians had whole-heartedly welcomed the memberships of Knights of Columbus, Masons, and Rotary Clubs, so there seemed no reason why the public could object when the Lions Club, a respected service organization dedicated to community-level charitable work with a particular emphasis on youth issues and disabilities, selected Toronto as the site of its international convention. With nearly 40,000 Lions Club members and their families lodging, dining, and entertaining themselves here, the four-day convention was expected to inject $2 million into the local economy.

Mayor Philip Givens, Metro Toronto Chairman William Allen, and Premier John Robarts enthusiastically accepted invitations to greet the assembled Lions delegates on the opening night of the convention. What, apparently, no one had counted on was the Lions Club’s tradition of inviting the governor of the international president’s home state to address their convention. Since Aubrey D. Green, Lions president in 1963-64, was from Alabama, this meant Governor George Wallace was scheduled to speak, immediately overshadowing the other keynote speakers like minister and author Norman Vincent Peale, and the information officer for NASA’s Project Mercury, Lt.-Col. John A. Powers.

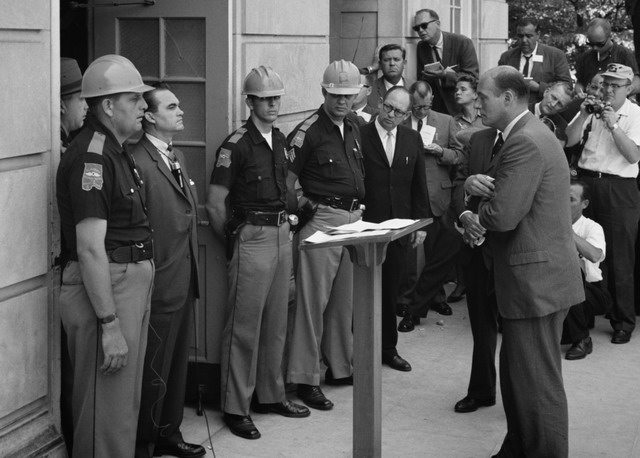

Once a lawyer and judge with a reasonably progressive record, Wallace won the office of governor in 1962 by espousing racist rhetoric and adopting an aggressively segregationist stance. With Alabama becoming a central battleground in the struggle for Civil Rights, Wallace cast himself as the public face of the Jim Crow South, literally blockading a doorway at the University of Alabama to prevent the enrollment of black students in June 1963, and rabidly opposing the Civil Rights Act a year later. Until his born-again conversion in the late 1970s, Wallace was the country’s primary spokesman for, as he’d once put it, “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

When it emerged that Wallace—who wasn’t even a Lion—was slated to appear, the first public voice of protest was that of Toronto businessman Herbert T. Barnes. Just a week earlier, Barnes had resigned from the local Optimist Club after a failed 15-month campaign to convince its international parent to remove all colour bias from its constitution. “If Canadian Lions feel strongly and are not apathetic about racial discrimination, they wouldn’t have him come here,” Barnes told the Star (June 24, 1964), urging his countrymen to boycott the convention unless the Wallace invitation was rescinded.

“Let him stay in the stinking South with his own people who think as he does,” James Pole-Langdon of the United Automobile Workers admonished at the July 2 meeting of the Toronto and District Labor [sic] Council. “We should not let people even hear the stink that he’s bringing to Toronto,” Jack White, a black member of the Iron Workers Union, insisted at the same meeting. “Many of my brothers in the United States have been deprived of the rights I am able to enjoy as a Canadian.”

Horace Brown, an alderman and representative of the Toronto Newspaper Guild, urged his labor council colleagues to direct their condemnation at Lions International rather than Wallace, who was merely “the invited guest of invited guests.” Emphasizing the politician’s right to speak, Brown added: “Are you going to tell everybody whose opinions we don’t agree with that they are not welcome in the city?”

The labor council asked the city to deny Wallace an official reception. The mayor and city officials, who wanted no part of the increasingly embarrassing situation, were relieved to side-step the controversy because the Lions had never formally requested civic honours for the Alabama governor.

Article from the Globe and Mail (July 3, 1964).

The Canadian Anti-Apartheid Committee (CAAC) went further, demanding that provincial and municipal dignitaries boycott the convention entirely “‘unless the Lions take a clear position on civil rights.” Robarts explained that he hadn’t known of Wallace’s invitation when he’d agreed to speak, and stressed that there would be “no official meeting” with Wallace. While he was “in complete disagreement” with the segregation of the American South, the premier rationalized, Wallace was “not here to discuss these things.” Like Givens and Allen, Robarts would fulfill his commitment to welcome Lions delegates at the opening of the convention.

A meeting of nearly 20 community organizations convened on the evening of July 3 to coordinate their opposition to Wallace’s appearance. Spearheaded by Rabbi Abraham Feinberg, a Jewish progressive labeled the “Red Rabbi” for his social activism, participants in this loose coalition included the labor council, the Toronto Labor Committee on Human Rights, the Toronto United Negro Association, the Home Service Association, the CAAC, and the New Democratic Youth. When the Lions leadership refused to meet with them, the coalition sent a telegram urging the executive to cancel Wallace’s appearance because he is “the symbol and spokesman of racism,” and began organizing protests.

Coverage of Green’s arrival from the Toronto Star (June 30, 1964).

After his arrival at Malton Airport on June 30, the Lions president remained defiant. “Gov. Wallace is a very distinguished, very warm, very humanitarian individual,” Green maintained. “He’s a Christian gentleman and enjoys wide respect. He is a strong believer in constitutional government and in states’ rights.” A car dealer and former state senator from Sumter County—a rural Alabama district where the Jim Crow mentality remained deeply ingrained into the 1980s—Green proved less-than-adept at handling the Toronto press. His response to one query, explaining that his hometown club had never considered admitting Negroes “because of the social structures and patterns of life” in Alabama, became a sensationalistic headline. Pressed by reporters to outline his personal stance on the just-enacted Civil Rights Act, Green tried to be diplomatic: “I have strong feelings on this, but will restrain myself from the luxury of comment out of deference to the fact that I’m the Lions International president.”

Although it’s not clear whether local clubs had any input in the decision, the Lions executive backed their president. In a resolution on July 6, the Lions deplored the “widespread publicity given current political subjects unrelated and irrelevant to the purposes of this association.” After reminding Torontonians that the service club had turned down appealing offers from other cities to bring their business to Ontario, the resolution expressed hope that “the great and friendly city of Toronto would extend a warm and cordial welcome to all its guests.”

Letters to the Editor from the Toronto Star (July 7, 1964).

“We have no colour bar in Lionism,” one prominent Lion from Newmarket claimed. Increasingly defensive, others pointed to delegates from clubs in Africa and Asia, as well as the numerous black Lions from Canada and the northern states as evidence their service organization did not have a problem with race. Who were they, club members seemed to ask, to ruffle the feathers of their Dixie counterparts?

But there were only 48 black members of Lions Clubs in North America, one newspaper estimated. Because Lions membership was by invitation only, local clubs exercised total autonomy over their own composition, utilizing whatever informal membership restrictions they wanted, with minimal interference from newly-enacted Civil Rights legislation that specifically excluded private clubs [PDF]. It’s also noteworthy that, at the 1964 convention, one candidate extremely upset that a false rumour he planned to end segregation in all Lions Clubs cost him the election to be third vice-president of Lions International—customarily the stepping stone into the presidency.

Adamant that their organization was apolitical and non-sectarian, many Lions were bewildered by their reception in Toronto. Hoping to underline the club’s non-partisanship, Green explained that Alabama’s Lions Clubs had spent more than $1 million on sight-related charitable initiatives “for the colored race” over the last 20 years. “In the area where I live there is much peace and harmony,” he added, without irony, to downplay civil unrest in the southern states. “Lions are doing a great deal in humanitarian service and it’s appreciated by all people.”

When Rabbi Feinberg appealed to the moral sensibilities of Lions members to “stand up and be counted at this crossroads in the history of man,” few listened. Most happily wandered around town in their distinctive hats and gold-and-purple jackets, unconcerned about the growing controversy. Only a handful, like Wilbert S. Richardson—past president and one of two black members of the Parkdale Lions—promised to boycott Wallace’s speech. “[I]t’s just unfortunate that our president is from Alabama,” Richardson added, underlining that he’d never experienced racial prejudice in the organization.

Article from the Toronto Star (July 7, 1964).

After their pleas to the Lions executive fell on deaf ears, the anti-Wallace coalition called for Torontonians to join mass demonstrations “to express their abhorrence of all that Governor Wallace has come to represent, and their determination not to permit his inhuman policies to creep in unnoticed.” Mrs. Jean Daniels, the elderly black woman who chaired the CAAC, was optimistic that at least 1,000 demonstrators would turn out. For the next few days, members of the New Democratic Youth hand-painted 250 anti-Wallace placards in a University of Toronto dorm, while another 60 were professionally printed by the Toronto Labor Committee on Human Rights.

Public opinion was divided. For every letter to the editor in Toronto newspapers lambasting Wallace as “a cocky racist” or “anathema to Canadians,” there was one imploring Torontonians to treat its guests hospitably and without criticism. “The ill-mannered harassment of Lions club officials…is not likely to endear this city to visitors and makes one ashamed of being a Torontonian,” one letter writer complained. “The Lions are Toronto’s guests during their convention. They are entitled to be treated with decency, respect, and courtesy. The choice of their speakers is strictly a club affair and no concern of Toronto people.”

In a passionate and eloquent open letter, published in the Globe and Mail (July 8, 1964), Rabbi W. Gunther Plaut of Holy Blossom Temple, was strident in his criticism of the governor. “You say that you are defending a way of life,” he wrote. “You are indeed. Only we happen to believe that racial privilege is not a defensible way of life, that, in fact, it is immoral, sinful, irreligious.” Yet he credited Wallace with energizing church and synagogue behind a common moral purpose: “In every community, denominations which yesterday could agree on little, now stand together, speak together, are together. In a way, we should be very grateful to you, for not only have you helped to give our religious institutions new vitality and have provided them with a great cause, but you have also brought us together and have given us one single great voice.”

Coverage of the Lions Convention Parade from the Toronto Star (July 8, 1964).

In advance of the convention’s official opening, the Lions International staged one of the largest parades in Toronto’s history on July 8. Thirty-five floats—each representing a Lions district—and 80 marching bands travelled a Yonge Street route from Queen’s Park to The Esplanade, watched by an estimated 250,000 Torontonians crowded six-deep on the sidewalk. Lions officials and their families travelled in white-coloured convertibles, and two uniformed state troopers drove a hard-top cruiser as representative of the State of Alabama. Waving from the Florida float, one young woman wearing only a bikini drew the whistles of spectators. Lions members from Kingston was joined by a pair of pet goats.

Despite the parade’s celebratory tone, even here the Lions could not escape the consequences of their Wallace decision. One float was vandalized with “Racists Go Home” scrawled across it in white paint. A solitary protestor, dressed in black hood and robes, marched ahead of the parade with a placard requesting social equality and harmony on one side. On the back, his sign read: “I am only one man. Do I walk alone?” And news leaked that Joseph Piccininni, a prominent club member and Toronto alderman who’d been selected to chauffeur the Lions International president during the parade, had been fired from the honourary post by Green after expressing dismay about Wallace’s appearance. Visibly upset, the alderman promised to boycott any convention sessions attended by Wallace.

Coverage from the Toronto Star (July 9, 1964).

That evening, as 14,000 delegates jammed into Maple Leaf Gardens, 1,000 protestors marched slowly along the sidewalk outside. Singing “We Shall Overcome,” and peacefully stepping aside to let delegates into the arena when directed by police, the demonstrators were a mixture of students, well-dressed businessmen, blue-collar tradesmen, and youth drawn from a variety of ethnic, political, and labour groups. Some parents carried toddlers on their shoulders. NDP MP David Lewis marched beside a man in an Abraham Lincoln costume. Several groups joining the pickets were not at all known for political radicalism—like the decidedly middle-class Canadian Negro Women’s Association (CNWA), which usually staged social events to raise funds for scholarships. “We were parading around outside the Gardens,” one CNWA member later said. “I recall I was very, very nervous but when I look back on it, it was a sort of positive thing.”

Signs demonstrators carried bore slogans like: “Wallace Racism Smears Lions,” “Lions—Put Civil Rights in Your Constitution,” and “Segregation Equals Apartheid.” As they had done during the parade, some protestors distributed pamphlets—bearing graphic photos of Alabama state troopers clubbing black protestors—to passers-by. “A lot of American Lions won’t take the leaflets,” one student activist observed.

After about an hour, the marchers moved to nearby Allan Gardens to hear speeches by former MPP and NDP organizer G. Eamon Park and Rabbi Feinberg, who for 18 years had been spiritual leader of Holy Blossom Temple. “Governor Wallace has carved a political career out of contempt for human beings,” the Rabbi said, “and we owe more courtesy to the Negro members of our community than we owe a second-hand guest.”

Coverage of protestors and Wallace’s arrival from the Globe and Mail (July 9, 1964).

A private plane with the Confederate flag and the phrase, “Stand Up For America,” emblazoned across the fuselage landed at Malton Aiport just after 7 p.m. Wallace emerged with his wife and companions to be greeted on the tarmac by one or two Lions, and the large security entourage composed of Metro Police, RCMP, and unarmed Alabama state troopers that would remain at his side for the duration of his visit.

Wallace’s motorcade hastened to the Royal York Hotel behind a police escort. As the governor was ushered through a crowd by police onto an elevator to the 17th floor, many onlookers booed and jeered—including some in Lions apparel—while a few exclaimed, “We’re with you, George!”

Though he refused a formal press conference, Wallace barked, “Protests—they don’t bother me,” in the direction of reporters. An aide added that Wallace welcomed pickets, provided they were peaceful and didn’t interfere with his freedom of speech.

Now fewer in number, the protestors were back manning their Carlton Street picket on the morning of the 9th, when Wallace was scheduled to speak. A handful of Lions crossing the picket into the arena expressed mild support for the demonstrators. One from Sweden told them, “I’m sorry for the whole damn thing,” and his colleague added, “We have already protested against his presence.”

Many, however, were aggravated, even enraged. A few accused the protestors of being paid agitators; others suggested Torontonians had bad manners. “It’s the most asinine thing I’ve ever seen,” a delegate from Decatur, Georgia, exclaimed. “Wallace isn’t here to talk about race matters.”

“It’s always easy to condemn something that’s thousands of miles away and doesn’t affect you personally,” added another Georgian. “How would you people like it if we started picketing the Canadian embassy in Washington protesting discrimination against Canadian Indians and Eskimos?”

Several protestors, including a pregnant member of the CNWA, reported being shoved aside as irate Lions stormed by. Canvassers for the Martin Luther King Fund collected more valueless Confederacy bills, garbage, and insults than actual donations—raising a paltry $625, well short of its $15,000 goal. At least one Texan was heard muttering to his wife as he walked by: “They look like a bunch of half-breed Communists.”

Granted a hearty welcome by Green before 12,000 or more Lions, the stocky governor strode to the podium to thunderous applause. Expressing gratitude to his Canadian and Toronto hosts, Wallace prefaced his remarks by stating that he didn’t want to discuss politics.

Then, he launched into a 15-minute-long tirade that ranged from the “tyranny” of the U.S. government and the “black-robed despots” of the Supreme Court, to the misrepresentations of the liberal press. “What do we call this form of government?” he bellowed, “It is not a democracy, for certain.”

Wallace was interrupted by applause at least four times, newspapers related, and earned himself a 30-second ovation led by the Alabama delegates. Not all delegates showed the same enthusiasm. And some, even on the stage, sat with folded arms. But no one in attendance booed. One New York delegate, however, contested this description of events, and claimed afterward that the only applause at all came from the representatives of the southern states.

Outside, the demonstrators dispersed while Wallace spoke. The governor was gone not long afterward, flying off by private plane less than 24 hours after he’d arrived. “When the Lions began to leave for home that afternoon,” Jack Batten concluded in Canadian Forum (August 1964), “most Torontonians…were glad to see them go and, I suppose, the Lions were glad to leave. It had been a strange unpleasant little encounter in the U.S. civil rights war.”

Responding to Wallace’s speech, the Star lashed out at those who’d accused the protestors of being inhospitable to the well-intentioned Lions and their guest. “Governor Wallace’s ‘non-political’ speech ripped aside the flimsy facade of respectability provided by the Lions,” the newspaper seethed. “There is no need to apologize for Toronto’s hostile reception to Governor Wallace and his poisonous doctrine.” The Star concluded: “If some of the hostility has rubbed off on the Lions they have only themselves to blame.”

Rabbi Plaut responded eloquently to critics of the demonstrations who’d rightly pointed out that the Deep South had no monopoly on racism and discrimination, expressing hope that Wallace’s visit would prompt Canadians to examine their own discriminatory policies and practices. “In fact, we owe you still another debt of gratitude,” he address Wallace in an open letter. “Your coming here has reminded us once again that we have unfinished business in Canada. We are more keenly aware that Eskimos and Indians have problems in the solution of which we have been less than assiduous. We have our own areas of discrimination and segregation in practice if not in law. We have practiced discrimination in our immigration policies, hiding behind mythical preferences of national origin. Your presence in our midst will help us tackle this unfinished business with greater speed and concern.”

Sources consulted: Jack Batten, “Toronto Greets the Lions,” in The Canadian Forum (August 1964); Keith S. Henry, Black Politics in Toronto Since World War I (Multicultural History Society of Ontario, 1981); Lawrence Hill, Women of Vision: The Story of the Canadian Negro Women’s Association 1951-1976 (Umbrella Press, 1996); Martin O’Malley, “Blacks in Toronto,” from W.E. Mann, ed., The Underside of Toronto (McClelland and Stewart, 1970); and articles from the Afro-American (July 18, 1964); Chicago Defender (July 11, 1964); Gadsden (Alabama) Times (July 8, 1964); Globe and Mail (May 16, June 24 & 25, and July 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15, 17 & 20, 1964); Montreal Gazette (July 8, 1964); New York Times (July 10, 1964); Ottawa Citizen (July 7, 1964); Toronto Star (May 19, June 23, 24 & 30, July 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 15 & 18, August 22, and September 18, 1964; August 2, 1969, and December 31, 1995); and Tuscaloosa News (July 12, 1960; and March 25, 2007).