By Craig Heron

On 30 May 1919 Toronto was bracing itself for a tumultuous labour confrontation. At 11 am unions started walking out in a city-wide general strike in support of an eight-hour day. Two weeks earlier 30,000 workers had hit the bricks in Winnipeg and completely shut that city down. Was that Toronto’s fate too?

To the great relief of the city’s businessmen and politicians, the answer was soon No.

At the beginning of May, the city’s twelve metal-working unions had started a strike. They were represented by a new Metal Trades Council, which insisted on joint bargaining with employers. Their bosses would have nothing to do with such a “one big union.” They also refused to discuss the metalworkers leading demand – an eight-hour day.

So on May 13 the Metal Trades Council asked the Toronto Trades and Labour Council to call a general strike in support of their demands, just like Winnipeg was about to do. The labour council decided to hold a special strike convention. Local unions would poll their members beforehand.

Meanwhile the cautious leaders of the labour council tried to head off a general strike. The mayor got involved in a week-long process of mediation between the metalworkers and their employers. And Prime Minister Robert Borden invited the parties to Ottawa for a day-long meeting to find a settlement.

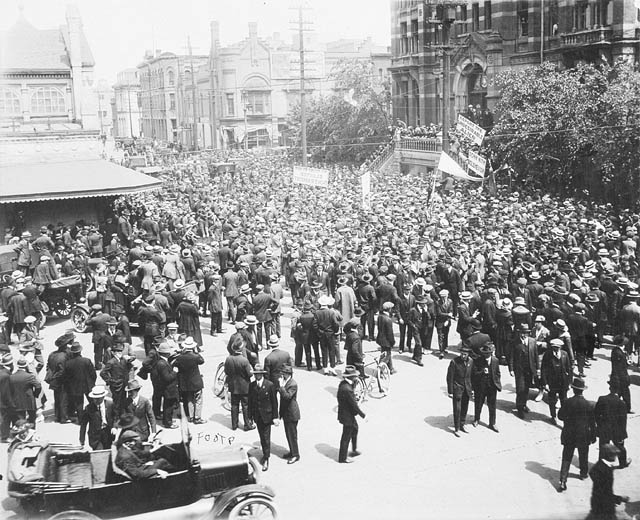

None of this broke the momentum toward a city-wide shutdown. As the president of the Metal Trade Council told a big rally at Queen’s Park, “the capitalists will get such a dose of Winnipegitis before this is over that they will never forget it.”

When the votes were counted, however, there was a two-to-one majority for the general strike, but more than half the votes were abstentions. Far too many workers were sitting on the fence. Their conservative leaders had flailed them with fears about broken contracts with their bosses.

So when the strike officially started on Friday May 30, the metal-workers were joined by only 3,000 carpenters and 2,000 garment workers. By Monday a few other unions had walked out, totalling perhaps 17,000, but crucially the street railway union and other city workers, as well as the large new packinghouse workers’ union, voted not to join. By Tuesday the Metal Trades Council realized there was little hope of anything more. That night the general strike was called off. The garment workers waited till the next day to return to work.

This crisis in labour relations had exposed a deep left-right split in the Toronto labour movement. At the annual executive elections for the labour council in July, the conservative leadership that opposed the general strike were swept out of office by a slate of left-wingers who had supported it. But the epidemic of “Winnipegitis” had passed.