By Craig Heron

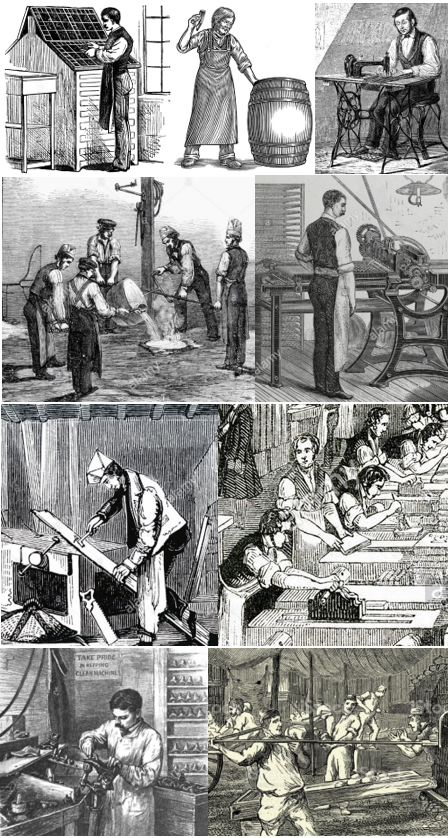

Printer, Cooper, Tailor

Moulders, Machinist

Carpenter, Bookbinders

Shoemaker, Bakers

GETTING STARTED

It was a bright spring Wednesday evening as small groups of men trudged up to the small hall on the second floor of 115 Bay St. The city’s iron moulders union had rented this space for their meetings and sublet it to other groups as needed. The clatter of the vinegar works and cigar-box manufactory downstairs had ceased for the day. Twenty-four men from seven local unions exchanged greetings and took their seats in the dingy space. John Hewitt, a cooper, walked to the front of the hall and called the meeting to order. It was 12 April 1871.

This was a follow-up meeting to one held in the same room two weeks earlier. At that time the coopers had reached out to all the existing unions in the city to see if there was any interest in forming a central organization. The men at that first gathering had decided to go back to consult their organizations and to report back.

WHO WAS THERE

Most of the seven unions who sent representatives on 12 April had been around for a while. Their members had come together as they sensed threats to their craft standards and traditions as firms got bigger and more capitalistic in their management. Several groups of workers had already fought difficult strikes. Some had linked up with larger organizations headquartered in the United States to give them more bargaining clout

The printers’ local union, the Toronto Typographical Society, dated from 1844 and had joined the International Typographical Union in 1866. The iron moulders had set up a local in 1857 and affiliated with the Iron Molders International Union three years later. The boot and shoe workers had a Cordwainers’ Society as early as 1854 and had merged into the US-based Knights of St. Crispin in 1869. Cigar makers had unionized in 1864 and joined the Cigar Makers’ International Union two years later. Independent unions of tailors and bakers had also appeared in the 1860s. And the coopers, the movers and shakers for a new central body, had signed on to the new Coopers’ International Union in 1870. A spirit was evidently in the air to reach out of their own craft jurisdictions to unite all skilled workingmen.

THE ASSEMBLY IS BORN

That spring night they voted to launch the Toronto Trades Assembly and elected the coopers’ John Hewitt as its first president. Workers in several US cities and in nearby Hamilton had adopted the term “trades assembly” for these bodies. They were intended for organizations of skilled white men. They made no room for common labourers whatever their race and ignored the wage-earning women who were starting to appear in larger numbers in the city’s shoe factories and clothing shops.

The trades assembly certainly did want to reach out to other skilled workers in Toronto, whether unionized or not. The delegates struck an organizing committee that reported considerable success over the next few months. They convinced several existing unions to join – machinists, carpenters, cabinetmakers, bookbinders, boilermakers, carriage-makers, painters, builders, hackmen (taxi drivers), watchmakers, hatters, blacksmiths, and even, briefly, dry-goods clerks. The committee also helped to start new unions among coach-makers, varnishers and polishers, upholsterers, bookbinders, tinsmiths, harness-makers, and plasterers. Not all of these survived. By the end of 1872 the trades assembly had fourteen organizations on board. By the end of 1874 there were sixteen, the largest number it ever included.

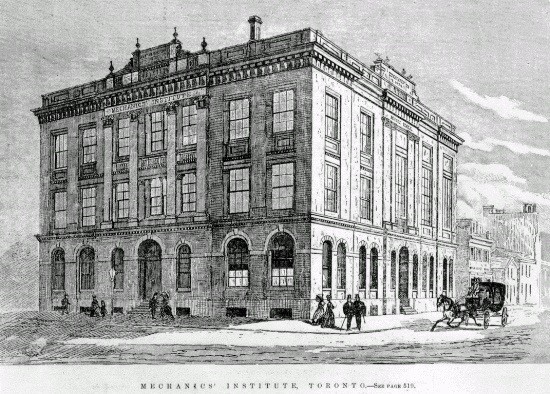

A CENTRAL MEETING HALL

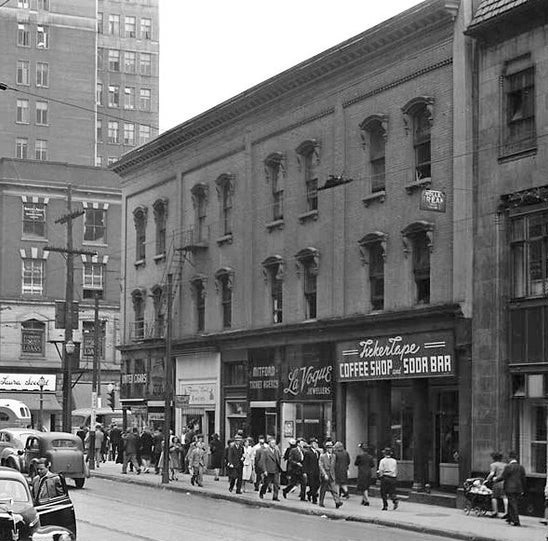

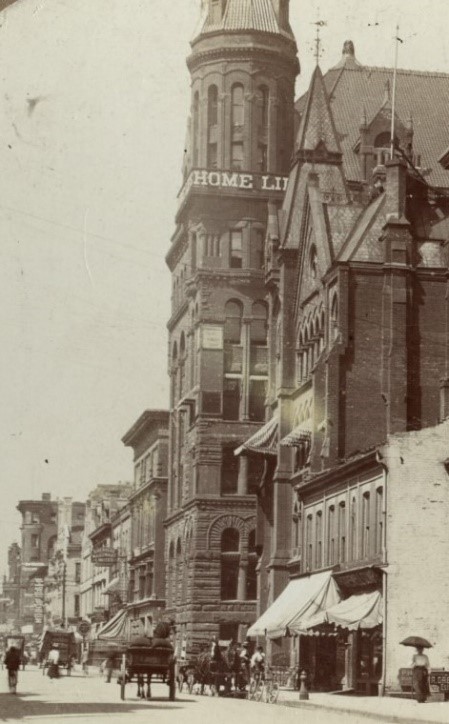

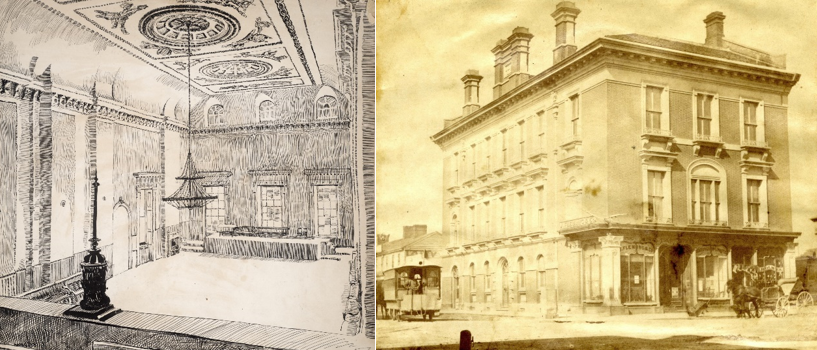

The trades assembly continued to meet every week or two in the moulder’s hall, but delegates were soon discussing how to buy or rent their own hall. After months of checking around, they agreed to rent one a two-minute walk away at 74 King St. West near Bay St. It was apparently a second-floor space on Toronto’s busiest street at the time, which was lined with ornate two- and three-story buildings. The city of 56,000 people was an undifferentiated jumble of houses, retail shops, workshops, factories, churches, theatres, and government offices. So the trades-assembly men found themselves rubbing shoulders on King St. with businesses and industries of all kinds and sitting across the street from the venerable Royal Lyceum Theatre. The moulders and shoemakers moved in furniture from their own halls, and, after a little sprucing up and the installation of a lighted sign over the door, the Trades Assembly Hall opened on 2 February 1872. To cover the $200 annual rent, affiliated unions (and a few other groups) were encouraged to rent space for their monthly meetings, on a sliding scale from $25 to $35 a year. Soon every evening was booked.

Two years later delegates were expressing their frustration with the state of the hall and its rising rent. A committee reported that new halls were being built a few blocks away on the north side of Adelaide St. just east of Yonge. That December the trades assembly took a lease on a hall with three rooms of varying sizes. For the rest of their existence they would meet at 10½ Adelaide St. East.

The trades assembly encouraged sociability with large picnics and moonlight cruises for workers and their families. It promoted discussion of reform with lectures by prominent speakers from outside Toronto. It started the country’s first labor newspaper, the Ontario Workman, in the spring of 1872. Eventually it would set up a small library for workingmen.

THE NINE-HOUR DAY

The Trades Assembly also held several mass meetings for workingmen to discuss important issues. In February 1872 it sponsored a large one on the nine-hour day.

Workers in this period were working ten to twelve hours a day, six days a week. A rising chorus of forward thinkers in Britain and the United States was arguing and organizing for shorter hours. The printers had been discussing a shorter workday since early January, and it was one of their delegates to the Trades Assembly, J.S. Williams, the newly elected assembly president, who introduced a motion for shorter hours. The assembly agreed that 54 hours should be a work week. On 14 February the mass meeting in the Music Hall drew a large gathering of what the Globe described as “respectable and intelligent looking men.”

John Hewitt introduced the motion that contained the essential philosophy of the emerging movement: the workingman was not benefiting as the Industrial Revolution unfolded. It stated that “the progress of the present age has brought into existence many useful labour-saving appliances that have greatly increased the production of manual labour,” but that “the producing classes have not received any benefit commensurate with the increase of production.” So, the motion said, “we demand the nine-hour system of labour as a right and shall use all honorable means to secure this end.”

Hewitt went on to argue that “Working men were now freemen and were entitled to the rights of freemen and not to be treated as serfs. They demanded that the labour of the world should be done in fair proportion, and that they should have a fair share of what that labour produced. They also demanded that the hours of labor be shortened.” More motions followed to reinforce that message that workingmen wanted a respected place in the new industrial age. They pointed to the need for more free time to allow workingmen to cultivate their intellectual interests and to fulfil their responsibilities as family men.

In a final motion the Trades Assembly invited “the hearty co-operation of all classes of our fellow working men interested in this movement.” It was stepping into the role of champion of the whole working class of the city. A few weeks later the assembly sponsored a public lecture by the prominent US labour leader Richard Trevellick on the virtues of the nine-hour day.

THE PRINTERS TAKE THE LEAD

Hamilton’s wage-earners had already formed a Nine-Hours League to co-ordinate such a campaign in that city, as several other cities would do, and unionists across the region were laying plans for a co-ordinated approach to demand shorter hours from employers in each city or town. Hamilton, it was proposed, would go first in mid May, and then Toronto would follow on 1 June. Under pressure from the printers, however, the Trades Assembly decided to let individual unions in Toronto take up the nine-hours banner on their own. The assembly would provide as much support as possible in these individual struggles.

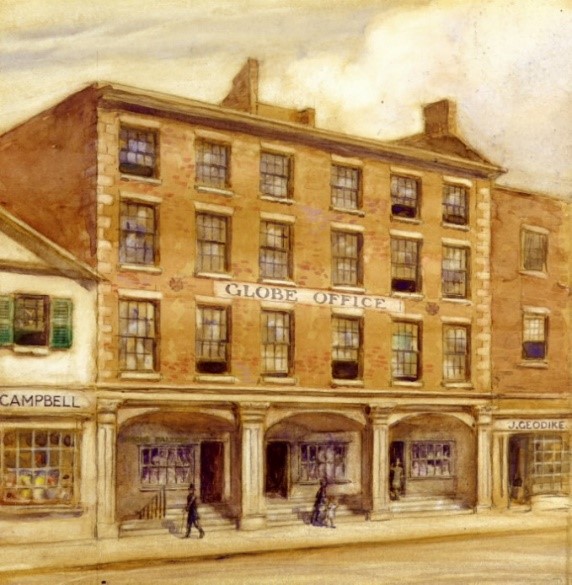

The printers’ union promptly announced its demand for a 54-hour week and gave their bosses a deadline of 18 March. After only one employer responded favourably, the printers walked out on strike on 25 March. A Master Printers’ Association suddenly appeared, as all newspaper publishers and job printers closed ranks to refuse the nine-hour day. Their leader was the publisher of the Globe and a “father” of Confederation, George Brown, whose office was just down the street from the Trades Assembly Hall. On 8 April Brown escalated his campaign of resistance by getting hundreds of Ontario employers to sign an open letter refusing to grant a shorter workday and denouncing the proposal as “a communistic system of levelling.”

INTO THE STREETS

The Trades Assembly gave the printers their full support. They passed a motion calling on “all tradesmen in the Dominion of Canada to give moral and financial support that may be required to frustrate the weak and foolish efforts made by the master printers … to annihilate the existence of Unions.” On 15 April they marshalled a huge, colourful parade of all the city’s unions with banners and marching bands, which ended with a rally at Queen’s Park and drew a crowd of 10,000 (despite a heavy snowstorm). The Ontario Workman claimed it was the largest demonstration in Toronto’s history.

AN ILLEGAL COMBINATON

The next day George Brown made his move. He got the fourteen printers who had been leading the strike arrested for criminal conspiracy under the common law. The legal status of unions was uncertain at best, and the bosses evidently believed they could break the strike by getting a judge to declare it illegal. The stakes were high: any group of union men who went on strike could be construed as an “illegal combination.” The assembly immediately held another mass meeting in front of city hall to denounce this union-busting. Four thousand men showed up. The case dragged on in front an openly hostile magistrate, who ruled that the men arrested should stand trial and released them on bail.

Meanwhile, however, the country’s prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, introduced a new bill in Parliament that brought the legal protection to Canadian unions that identical British legislation had created the year before. On 14 June the Trades Unions Act was passed. Brown’s case promptly fell apart.

Yet, after weeks of picketing, the strike was faltering and printers’ union membership was tumbling. The employers never jointly conceded the nine-hour day, but in negotiations with individual firms the union effectively made the 54-hour week a fixed part of their contracts. Meanwhile, the broader nine-hour movement had petered out. The Trades Assembly debated holding another mass demonstration that, it appeared, would be tantamount to starting a general strike. But delegates pulled back from that option, and ultimately took no more action.

GETTING POLITICAL

Toronto’s unionists had learned the importance of broader solidarity, however. On 2 May they had sent delegates to Hamilton to participate in a meeting of unionists from around the province to create a new Canadian Labor Protective and Mutual Improvement Association. John Hewitt was elected vice-president. This organization languished after one meeting, but a year later the Trades Assembly began reaching out to unions in other cities to revive the initiative. On 23 September 1873 a large gathering convened in Toronto and founded the Canadian Labor Union, the country’s first “national” (actually regional) central labour body. It would hold annual meetings until 1877.

The Trades Assembly had already begun lobbying provincial and federal governments for more favourable legislation. The Canadian Labor Union joined these campaigns for abolition of prison labour, revision to the Mechanics’ Lien Law, electoral franchise reforms to allow more workers to vote, repeal of the Criminal Law Amendment Act to remove the criminalization of picketing, changes to immigration practices, and reforms to the Master and Servant Act so that a disobedient worker would no longer be a criminal. Labour now had a political organization, and some determined Toronto’s unionists provided the leadership.

UNEMPLOYMENT TAKES ITS TOLL

The Toronto Trades Assembly continued its ambitious activities until 1878. The economic depression that has set in five years earlier was taking its toll on unions, as unemployment robbed local unions of members. Many folded their tents and disappeared. The local labour movement could no longer sustain a central organization, and the assembly stopped meeting.

In its seven-year history, the Trades Assembly had made a major impact on the economic, social, and political life of Toronto. And it had established a model for building solidarity across occupational lines that would be taken up three years later by a new Trades and Labor Council.